Major Strikes of the Late Nineteenth Century

"The conduct of of slate manufacturers in the past does not justify us in looking to them for the betterment of that condition, as we have not been treated by them as men." - workers at a South Poultney meeting, 1894

Overview

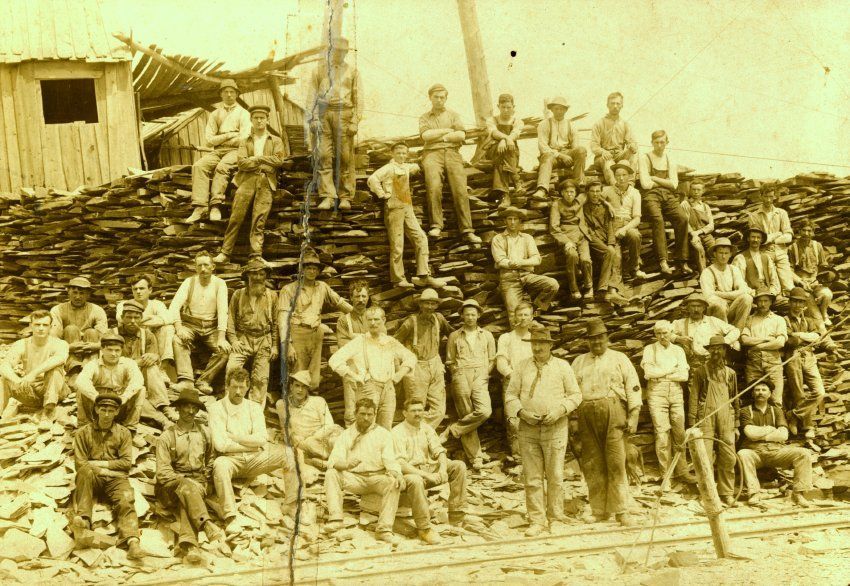

The late nineteenth-century was characterized by several brief strikes and a few major strikes. At this time workers were beginning to understand the power of collective organizing, though they often chose inopportune moments to strike and the economic panic of 1893 sent shockwaves throughout the slate industry that affected workers and quarry owners alike. Despite the many failed strikes throughout the late nineteenth century, the strike of 1894-1895 was a rare victory for the hundreds of striking workers.

Strike of 1883

Causes

The strike of 1883 began after the Slate Manufacturers’ Association announced that beginning on November 1 they would begin paying workers by the hour instead of the day. This ended a sixty year Welsh tradition called the “King,” in which workers would work a half-day on Saturdays but would be paid for a full day. Many workers worried that this new system would lead to mandatory shifts on Sundays (the day of rest) to fill special orders. On November 1st, workers in twelve quarries struck against this new policy. However, some workers argued that being paid by the hour would be beneficial to workers, especially ones that were forced to miss their Saturday shift, or came in late to work.

Strike Demands

The workers formed an impromptu union with elected representatives from each quarry involved in the strike. Workers demanded an abolishment of the hourly pay system to preserve their “king.” While some workers were willing to accept a 12¢pay reduction in the winter, a time that was notoriously slow for the slate industry, the vast majority stuck to their one demand to preserve the “king.”

Consequences

In a pattern that will be repeated, the workers chose a terrible time to strike. The winter months were usually slow for the slate industry, and quarry owners were happy to close their quarries until work picked up again. In addition, there was an oversupply of slate at the time so there was little incentive to produce more over the winter. The strike lasted only a few weeks as the, often, destitute workers could not afford to go without pay for an entire winter. Their demands were not met, and within the next few years quarry owners

would institute wage limits and agreed to not poach workers from each other. The burgeoning workers’ union disappeared and no significant union existed during the rest of the 1880s.

Strike of 1887

Causes

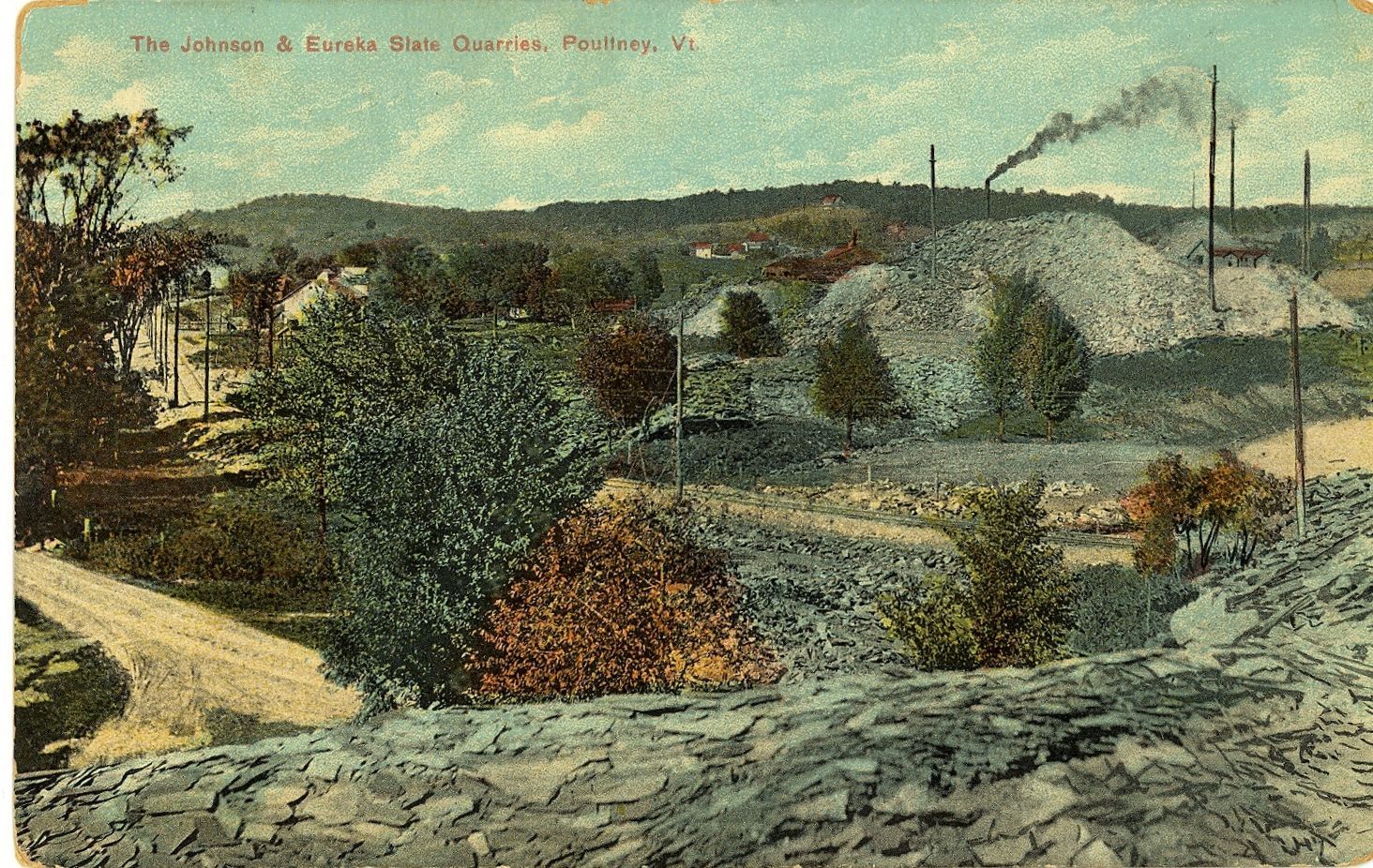

After the nationally powerful Knights of Labor came to the slate valley, many quarry owners became worried at the prospect of a new labor union meddling in their affairs. As a response the Evergreen quarry fired at least one worker for his membership with the Knights of Labor. In addition, the Billings Slate Company in Hydeville forced all members of the union to sign contracts stipulating that they would “work steadily for at least one year,” effectively removing their ability to strike.

Strike Demands

The workers had no specific demands, but instead decided to strike in solidarity with their colleagues that had been singled out for their union membership.

Consequences

The strike lasted only a few weeks, and ended in defeat for the workers. Many strikers were discharged, and others returned to work without any concessions from the quarry owners. The ineffectiveness of the Knights of Labor became apparent and the union faded from public awareness. The workers continued on without union representation. While at the time anti-union activities were legal, this would be made illegal by the National Labor Relations Act in 1935.

Strike of 1894

Causes

In 1893 a steep economic downturn occurred in the United States, which affected nearly every sector of the economy. The slate industry was no exception, and many quarries were forced to close as a result. The economic downturn was so fierce that the powerful Vermont Slate Trust dissolved. Many workers had spent much of the 1893 winter unemployed, so when quarry owners instituted a 3¢per hour wage reduction in Spring 1894, over 200 workers met in South Poultney and decided to strike. Later, in September of 1894 another wage reduction of 2¢per hour was announced and further enflamed the workers. Later, workers attempted to end the “Doctor’s Club” which forced monthly payments to a fund which acted as a sort of health insurance, however quarry owners refused and expected continued payments. Technically, the by-laws of the quarries allowed the workers’ to decide to end the “doctor’s club,” however quarry owners refused to recognize this.

Strike Demands

Workers argued that while they had not shared in the profits of prosperous times, they were being asked to sacrifice pay during desperate times. They demanded that wages be preserved at levels seen the previous summer; they also sought the establishment of a quarrymen’s union. As the strike continued they would later demand the abolishment of the “doctor’s club,” preferring instead to contribute to a health fund overseen by their union. This new fund would allow greater freedom in selecting doctors, something that the quarry sponsored “doctor’s club” did not allow. The workers also argued that the benefits they received from the “doctor’s club” were not worth the payments they were forced to make.

Consequences

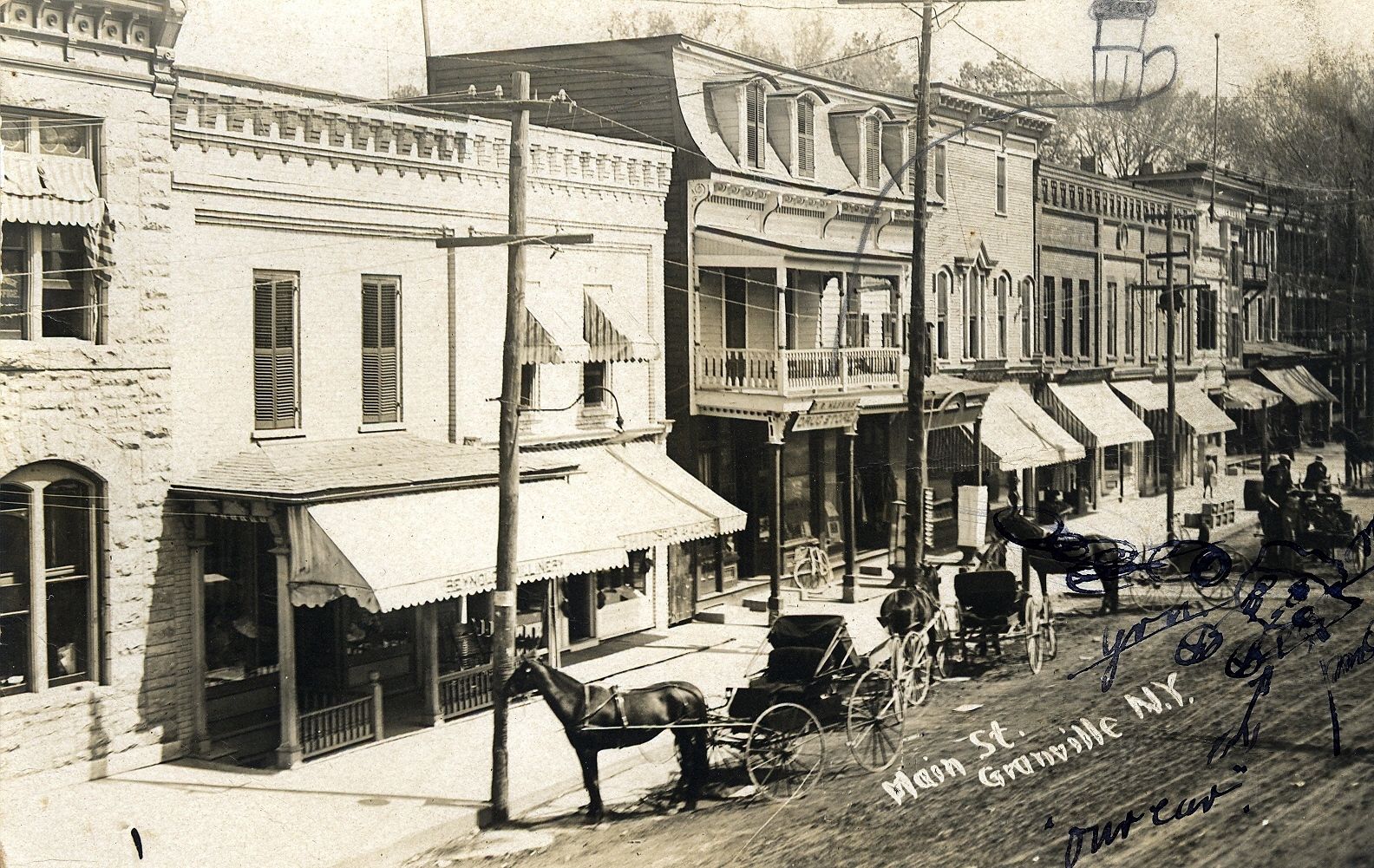

An initial failed strike in the spring lasted only a couple weeks, and workers returned to their jobs at the reduced pay rate. However, after the second wage reduction in September tensions flared again. In December, the union’s demand to end the “doctor’s club” resulted in an explosive situation after quarry owners rejected their bid to end the club. The workers again struck at an inopportune time, however, this time they appealed to the public for financial support to continue the strike. They received $681.08 which allowed them to continue their strike much longer than previous strikes. In mid-January, after seven weeks of striking, William H. Hughes (heir to the “Slate King of Granville’s” estate) agreed to end the doctor’s club. However, the Rising and Nelson quarry continued to resist striker demands, a decision which ended in violence in early February of 1895 when Harmon Nelson shot a revolver into the air in front of 300 striking workers. Nelson was then beaten and sent out of town on a train, with the warning to never return. Reportedly, Harmon Nelson moved to Wales and never returned to the United States. Three months later the strike was ended after the Rising and Nelson quarry agreed to end the doctor’s club.