THE WELSH

Skilled Quarrymen Form Labor Hierarchy

Consultant: John S. Ellis, Ph.D., Assistant Professor of History, University of Michigan, Flint, Michigan

Culture

The Old Country: Culture

Although incorporated into the English state, the rocky highlands of Wales proved an obstacle to the Anglicizing influences of English culture. As late as 1900, the majority of the population spoke Welsh as their first language. The rich poetic tradition of the Welsh language was reinforced by the cultural institution of the eisteddfodau, literary and musical competitions held at the local and national level. Unlike other Celtic languages, Welsh became a medium of print culture widely utilized in newspapers, magazines and books. Religious dissent from the official, state-sponsored Church of England (or Anglican Church) found fertile ground in Wales. Including such sects as the Baptists, Congregationalists and indigenous Welsh Calvinistic Methodists, Protestant nonconformity was the majority faith of the Welsh nation at the time of the emigration to the Slate Valley. Being outside the established Church, Welsh nonconformists were still forced to pay the hated Church tithe and suffered from a variety of civic and legal penalties.

New Lives: Culture

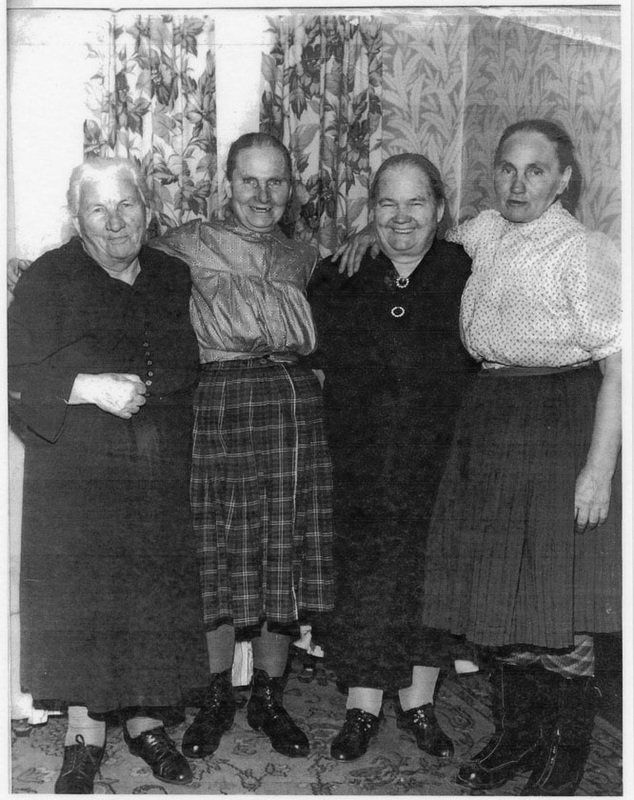

As in Wales, the Welsh language and the nonconformist chapel were integral parts of Welsh-American life in the Slate Valley. Effectively transplanted to American soil, the cultural institutions of the eisteddfod, cymanfa ganu and cymanfa pregethu were widely and frequently held in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. The valley became known for its many outstanding choral groups and choirs. Equally important to local Welsh culture were the many poets from the valley who published their works in Welsh-American periodicals like Y Cyfaill and Y Drych. Religious worship was observed through the medium of Welsh and the chapel provided guidance on almost every aspect of the immigrant's lives. Thirteen chapels served the Slate Valley’s leading Welsh denominations – the Welsh Calvinistic Methodists and Congregationalists. Communication and exchanges between Wales and scattered Welsh-American communities across North America were facilitated through a national Welsh-American press, nationally based religious and social organizations and national cultural events.

Next Generations: Culture

Although close-knit and speaking a foreign language, the Welsh were literate Protestants who were at least familiar with the English tongue. Consequently, Welsh immigrants were generally well received and integrated relatively swiftly into American life, a trend reflected in the union of the most distinctly Welsh denomination, the Welsh Calvinistic Methodists, with the Presbyterian Church USA in 1920. After the First World War, the vitality of Welsh language culture in the United States as a whole began to wane. The language was more resilient in the Slate Valley, where it continued to be commonly used in pulpits, choirs and on street corners as late as 1950. Despite their integration and the gradual loss of the Welsh language, Welsh-Americans in the valley remain highly conscious of their ethnic roots and proud of their cultural heritage.

Economics

New Lives: Economics

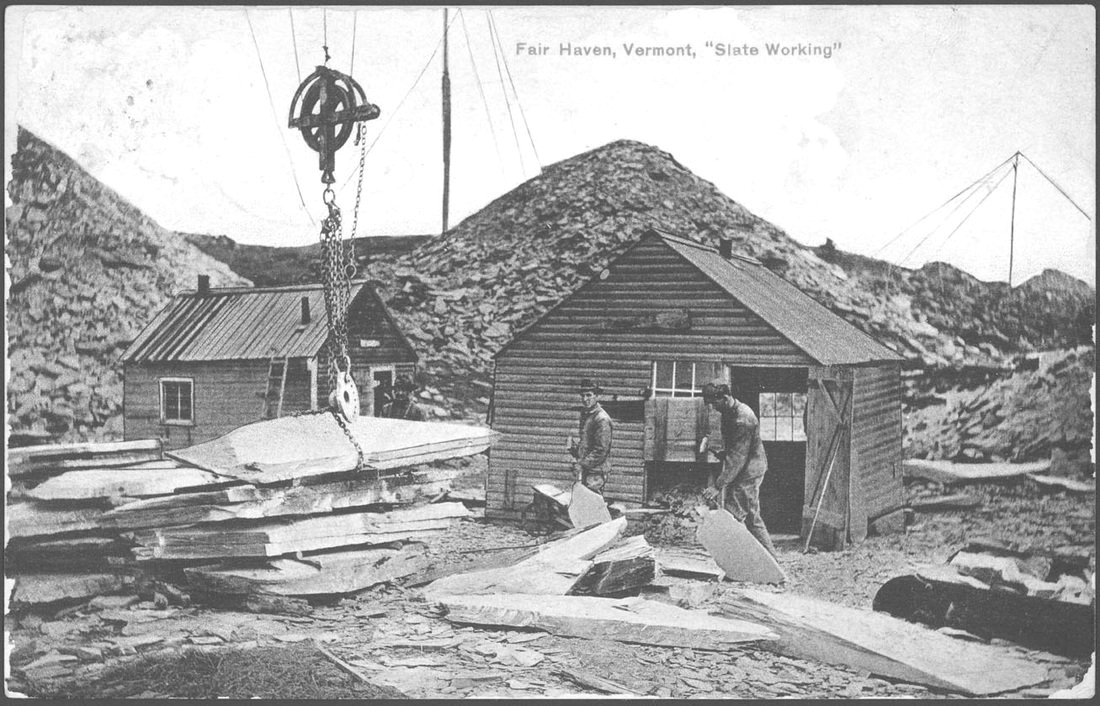

Although much of Wales remained agricultural, the industrial revolution transformed the region through the rapid development of coal mining in the southern valleys and slate quarrying in the northern mountains of Snowdonia. Wales held the largest slate quarries in the world, employing 16,000 at its peak in 1889. The industry, however, suffered from wide swings of expansion and contraction. The slate industry often replicated Wales’s rural division of landlords and peasants, where Anglican aristocrats owned the quarries and Welsh peasants on the lord’s estate provided labor in the pits and mills. Work was hard, wages low, employment insecure and resentment rife under the iron hand of draconian aristocrats like the Lords Penrhyn, the greatest family of quarry operators in Wales. The heated but failed strikes of 1885-86, 1896-97 and 1900-03 intensified the increasingly embittered industrial conflict in north Wales.

The Old Country: Economics

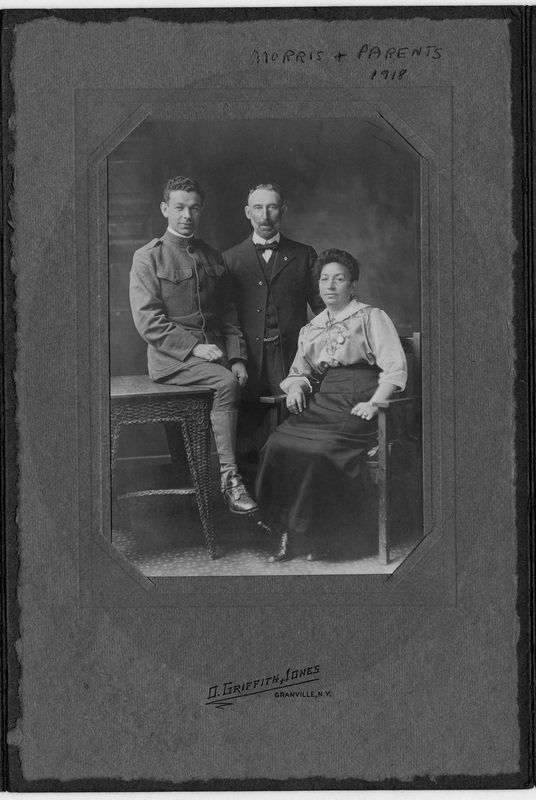

Fleeing the low pay, feudal nature and industrial strife of their homeland, the Welsh came to the Slate Valley from the 1850s through the 1920s. In an emerging economy, the nascent American slate industry recruited Welsh migrants with the necessary skill to open and exploit the valuable slate seams of the valley. As experienced and knowledgeable quarrymen, the Welsh often enjoyed a privileged position in this difficult and hazardous industry. They numerically dominated the labor force and they often occupied the higher paying positions in the quarry, making up the ranks of the skilled workers, supervisors, labor leaders and small-scale quarry operators. Transcending the bounds of their class in their new American home, some Welsh workers even achieved the status of wealthy owner-operators. Although the Welsh were often at the forefront of worker organization and agitation, the value of Welsh skill created a clear and at times strained division of labor in the Slate Valley with newly arriving bands of Eastern European and Italian immigrants providing the unskilled and poorly paid labor of the quarries.

Next Generations: Economics

Although Welsh immigrants and their American born sons still provided more than half the labor force in the slate industry as late as 1920, the Welsh often used their skills and advantages to ensure that their sons would not have to continue working in this difficult and dangerous occupation. During times of economic slump in the industry, Welsh migration away from the Slate Valley was endemic. The low demand for slate and the high wages offered by the munitions industry led to a significant exodus of Welsh workers from the valley during the First World War. Welsh immigration to the valley declined rapidly after the war and the Welsh-American community was especially hard hit by the collapse of the slate industry during the Depression.

Education

The Old Country: Education

The Welsh had little exposure to formal public education in the nineteenth century. “National” schools closely tied to the Anglican Church and heavily subsidized by wealthy landlords dominated public elementary education. Requiring a small tuition, these schools taught English and mathematics and required students to attend Anglican services and learn the Anglican catechism. Not surprisingly, Welsh dissenters avoided the schools. Inadequate schooling in north Wales was exacerbated by the tendency of boys to leave elementary school early to work in the quarries and contribute to the family income. Yet many Welsh workers could read and write. Most education took place through the chapel Sunday school, combining a basic education in reading and writing with religious and moral instruction.

New Lives: Education

The American public school system offered greater access to education in English, mathematics and other subjects than immigrants could find in Wales. Yet, the parallel education provided by the Welsh Sunday School continued amongst the Welsh immigrants of the Slate Valley. While the secular school system provided by the state provided formal education, Sunday schools sponsored by Welsh chapels instructed the immigrants, their children and grandchildren in the Welsh language, religious studies, moral instruction, geography and the traditional arts of Welsh singing. No more the principal source of education as it was in Wales, the Welsh Sunday School continued to play an important role in cultivating the cultural life of the old country in the new soil of the Slate Valley.

Next Generations: Education

Successful Welsh quarrymen and quarry operators pushed their sons to pursue the many and diverse opportunities that their new lives in the United States offered. Consequently, the Welsh-American population of the Slate Valley is only a small remnant of that which peaked in the early years of the twentieth century. However, the Welsh presence amongst the population remains a strong element in the character of the region. The Welsh no longer dominate the industry, but there are still Welsh-American quarrymen and quarry operators exercising the traditional skills of their ancestral homeland in the Slate Valley today.