THE SLOVAKS

Laborers Inherit The Industry

Consultant: M. Mark Stolarik, Ph.D., Professor and Chairholder, Chair in Slovak History and Culture, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada

Culture

The Old Country: Culture

From the eleventh century to 1918 Slovakia was an integral part of the multinational Kingdom of Hungary in Central Europe. The Slovaks lived in the northern arc of the Carpathian Mountains, in the shadows of the High and Low Tatra mountain ranges. Even though the Slovak population predominated in northern Hungary, it shared the territory with Magyar administrators and gentry, with German burghers in the cities, with Jewish shopkeepers in the villages, and with Roma (Gypsy) and Rusyn neighbors in the east. The Slovaks were divided into four religious denominations—the majority Roman Catholics (about 70%), Lutherans (about 15%), Greek Catholics (about 10%) and Calvinists (about 5%), each of whom worshipped differently in their own churches. The Slovaks spoke many dialects, which linguists have grouped into three main kinds—western, central and eastern. Slovak linguists codified the central dialect into the literary norm in 1846 and began to create a literature in it by 1851. The net result of all these influences was a culture that was very heterogeneous.

New Lives: Culture

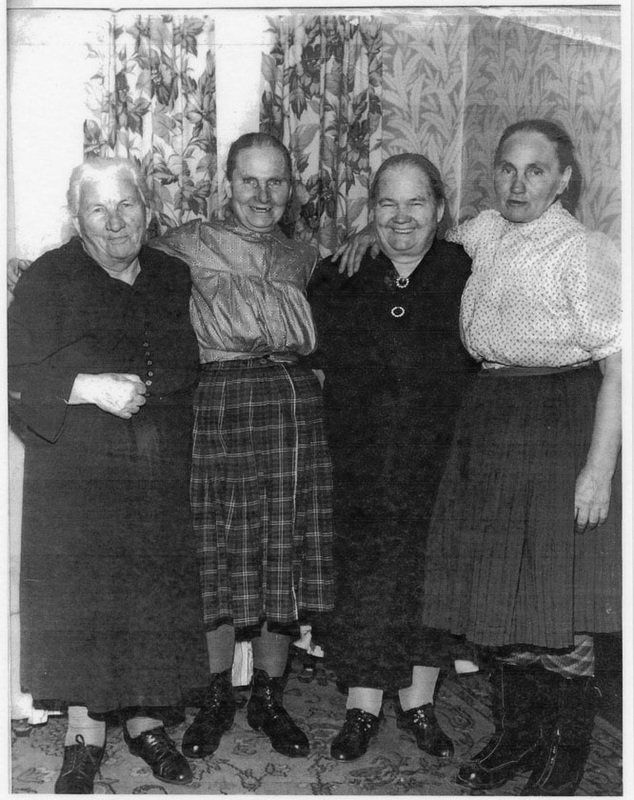

Slovak culture in the United States revolved around fraternal-benefit societies, churches and newspapers that used the Slovak language for the first two generations of Slovak-Americans. Shortly after their arrival in the New World they realized no social safety net existed, and they quickly established fraternal-benefit societies that would pay a sick or injured member some compensation, or else a death benefit to a widow or family if the husband were killed in an industrial accident. These societies sprang up in all Slovak-American settlements, and, starting in 1890, began to federate into national organizations. The societies also led the way in the establishment of Slovak parishes. In Granville, the Hungarian Society of Granville established Saints Peter and Paul Byzantine Catholic Church on Church Street in 1902. This church, plus the various fraternal-benefit societies that met on a regular basis in its basement, became the center of Slovak cultural life in the community. The church provided the sacraments marking the rites of passage with community celebrations.Through the church, Slovaks celebrated in an elaborate manner many religious holidays, especially Easter and Christmas, with centuries-old rituals. Meanwhile, the fraternal-benefit societies sponsored dances, plays, sports and other entertainment.

Next Generations: Culture

The first generation of immigrants raised their children in one of the eastern Slovak dialects and had them participate in all the rituals of the Greek Catholic Church. However, the activities of subsequent generations revolved less around the church and the fraternal-benefit societies. In the last decades, the number of parishioners at Saints Peter and Paul Byzantine Catholic Church has dwindled as members of the third and fourth generations have left the area for opportunities elsewhere or have joined other churches. These generations for the most part never learned to speak Slovak. Therefore, Slovak-language publications, and even the Greek Catholic Mass, sung in ancient Church Slavonic, have become increasingly irrelevant to them. Similarly, membership in various fraternal-benefit societies has also declined precipitously as cheap and easily available insurance plus other entertainment options have made the organizations less attractive.

Economics

The Old Country: Economics

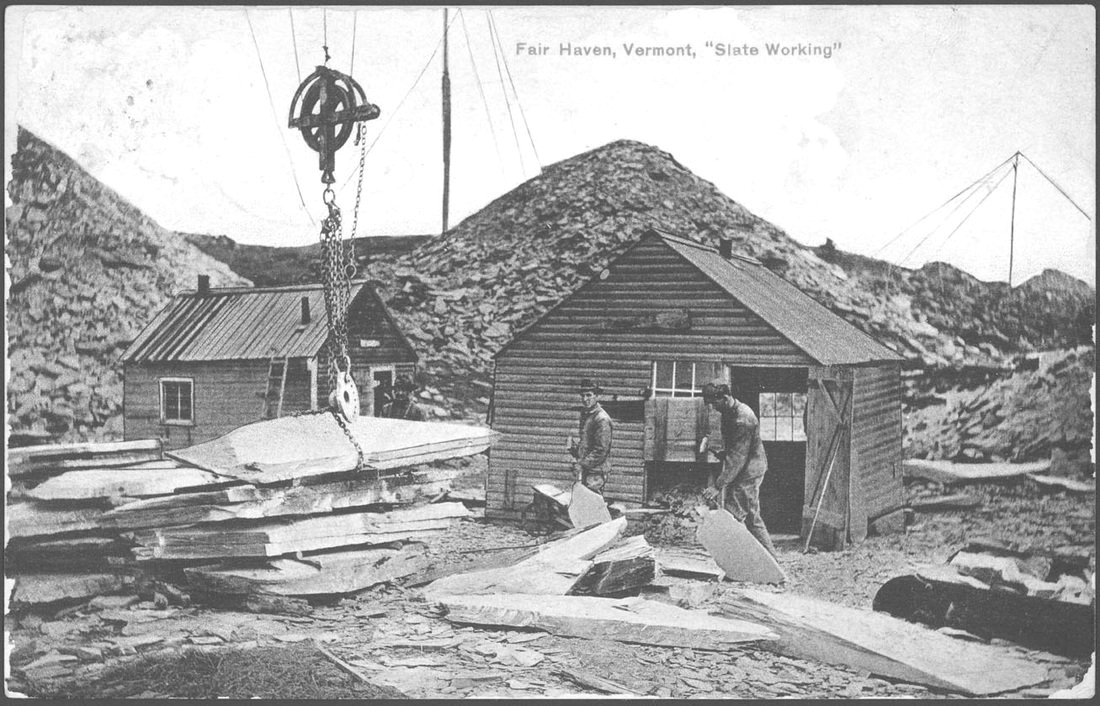

The vast majority of the Slovaks were peasants, most of whom had been freed from serfdom only in 1848. They worked tiny plots of land that, due to the practice of partable inheritance, soon became too small to sustain a family. The Slovak gentry was largely assimilated into Magyar language and culture in the nineteenth century and the tiny Slovak middle class consisted largely of priests and pastors, who, by default, became the political leaders of the nation. Most of the Slovak peasant men began to wander down to the Hungarian and Austrian lowlands, which had been reorganized into the Dual Monarchy of Austria-Hungary in 1867, in search of agricultural work. By the 1880s their search for employment had brought them to the industrial heartland of America. Here they found unskilled work in the coal mines, steel mills and oil refineries of the Northeast. Their wives, meanwhile, were left at home to take care of their children and the small amount of land that they could cultivate. By 1920 over 600,000 first and second generation Slovaks lived in the United States—almost a third of the population of their native land. The majority had come from eastern Slovakia. A few hundred were lured by agents at Castle Garden and later at Ellis Island to the slate quarries of New York and Vermont.

New Lives: Economics

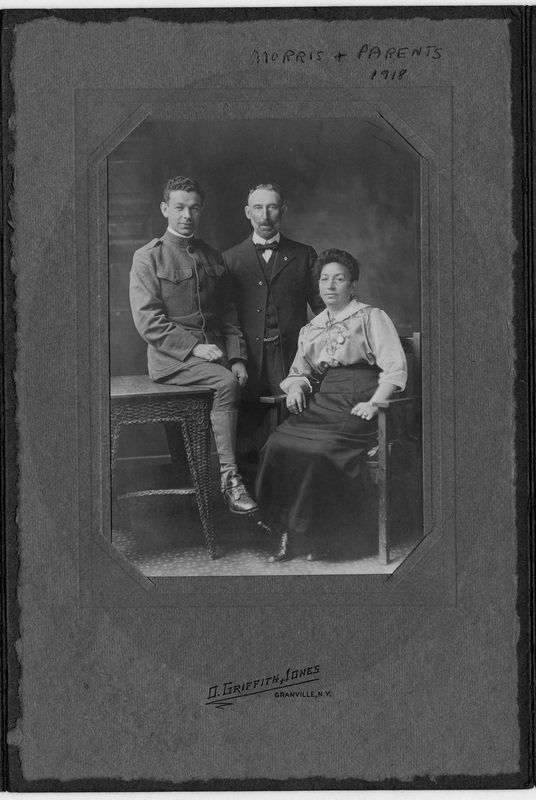

When Slovak men began to arrive in the Slate Valley in the 1890s, they filled the growing demand for laborers to work in the pits where the jobs were the most dangerous and the lowest paid. Second only to the Welsh in workforce numbers, they agreed to work in the pits at a mere 12 cents per hour, while their skilled Welsh and Irish supervisors earned over 20 cents an hour. Initially most of the Slovak immigrants were young, single or recently-married men who had come to America hoping to make their fortunes and to return home, buy some land and become yeoman farmers. They were promised good jobs and housing, which turned out to be crowded tenements like those on River and Water Streets in Granville, N.Y., unsympathetically labeled “Hun Alley.” A few of the wives followed them to America and took in boarders to help with the family income. The Slovak women acquired more authority in their new lives because they often held the men’s earnings, and if they took in enough boarders, they could earn as much in a week as their husbands.

Next Generations: Economics

As the American-born Welsh and Irish left the quarries in growing numbers in the teens and 1920s to pursue other occupations, the Slovaks replaced them, particularly in the southern part of the Slate Valley. Slovak boys at the age of 15 could be found working side-by-side with their fathers right up to the Great Depression in order to help support their families. In the 1930s most of the quarries closed and the Slovaks, like many others, suffered from unemployment. Through frugality and their resourcefulness in living off the land, some Slovaks stayed in the Slate Valley. After World War II they regrouped and bought 17 of the 30 quarries that remained open, and became successful quarry operators who have sustained the industry through boom and bust times. So it was after several difficult decades of contributing their hard labor that the Slovaks rose from the pits and crowded boarding houses to improve their financial well-being and to become respected by other members of the Slate Valley communities.

Education

The Old Country: Education

Education in Slovak and even the introduction and use of standard Slovak in nineteenth century Hungary were problematic. Starting in 1867 the ruling Magyars sought to assimilate all the non-Magyar ethnic groups in the Kingdom into Magyar language and culture. The government proclaimed that Magyar was the official language of Hungary and shut down all Slovak high schools and most Slovak grade schools, turning them into state institutions. By 1914 most education was in the Magyar language, which helps to explain the high level of illiteracy, 30-50%, among Slovaks, depending upon the region. The government also severely restricted the publication of Slovak newspapers and other periodicals. It fostered the use of Magyar in church services. It was this kind of suppression that made Slovak immigrants to America determined to preserve their language and customs through their own institutions once they could afford to do so.

New Lives: Education

Soon most Slovak Catholic parishes in America established their own parochial schools where, besides the regular curriculum in English, reading and writing in Slovak as well as Slovak history and culture were also taught. If they could not afford to establish their own school, then the parents would send their children to the local public school. In such cases, Slovak parents usually arranged for the priest to conduct Saturday morning classes in Slovak for the school children. Slovak immigrants to the Slate Valley who had not learned to read in Hungary learned to do so usually from someone in the boarding house who read the Slovak newspaper when it arrived. Before the Great Depression of the 1930s, American-born Slovak boys in the Slate Valley usually finished only grade school and then went to work in the quarries.

Next Generations: Education

While members of the second generation of Slovaks seldom went to high school before the Great Depression, they started doing so in the 1930s. After World War II, aided by the G.I. Bill, Slovaks began to attend universities in greater numbers. While many college educated Slovaks moved on to white-collar and professional occupations, others returned to continue the family slate companies or to start their own.