THE ITALIANS

Poverty Leads to Entrepreneurship

Consultant: Salvatore Primeggia, Ph.D., Professor of Sociology, Adelphi University, Garden City, New York

Culture

The Old Country: Culture

In the traditional patriarchal Italian society, social roles and social position were clearly defined and stringently upheld. The people were parochial and their vistas were limited by campanilismo (the boundaries set by the sound of the village bell). The family was the primary social institution that bound all members to it. Religion played an important role in the lives of the Italians. While women were devout followers of their Catholic faith, the men most often were opposed to the formal church structure. However, even the men would become involved participants in the feste (feasts) that honored their local patron saint or madonna.

New Lives: Culture

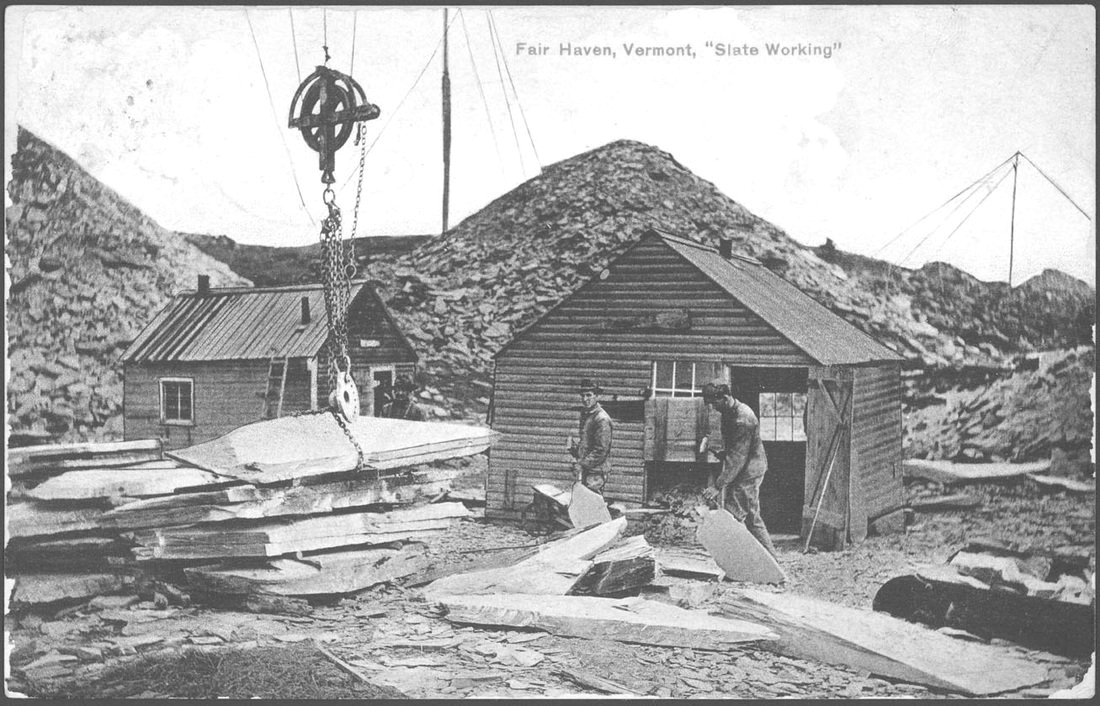

Push-pull factors were the causes of Italian migration from Italy to the United States at the turn of the twentieth century. While the vast majority of Italian immigrants stayed in the cities, a smaller portion made their way to the rural areas of America. Some worked on farms while others were drawn to the quarries, including those of the Slate Valley. For the first generation Italian-Americans, they wished to maintain the values, traditions, rituals, and way of life of the Old World and pass them on to their children. The solidarity of community they created in the Slate Valley and elsewhere helped the Italians in America sustain themselves in dealing with the prejudices they encountered in the New World. Part of their safety net was their unique religious belief structure that was brought to the New World and sustained them. The folk-religiosity of pre-immigration Italy was transposed by the immigrants to the different Italian-American communities. The combination of Catholic orthodoxy with superstitious beliefs as well as the strong devotion to specific patron saints and madonnas continued to sustain the immigrants and their children in America.

Next Generations: Culture

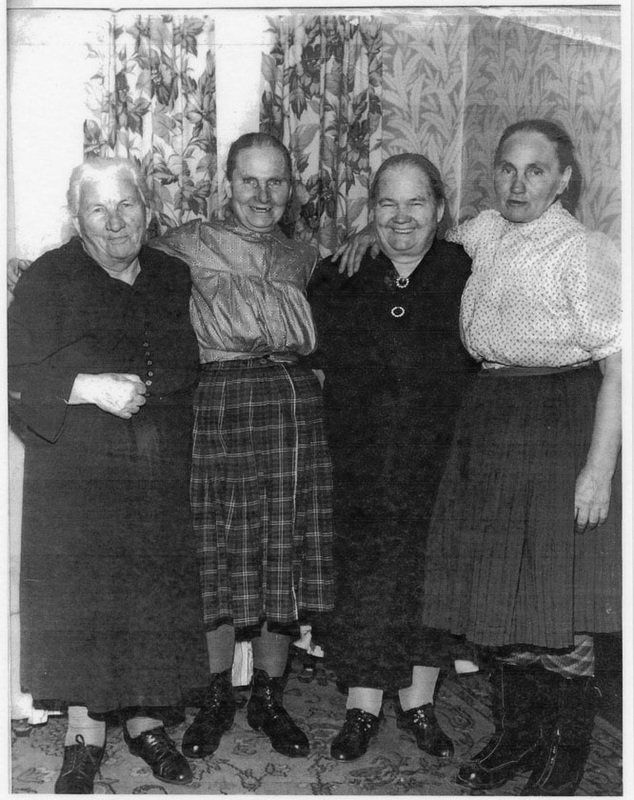

Starting with the second generation of Italian-Americans in the Slate Valley, there was the attempt to combine the strongest elements from the American and Italian cultures. The children of the immigrants, as well as the grandchildren and great grandchildren, became Americanized without jeopardizing their Italian roots, traditions, values and beliefs. While the religious practices of the descendants of the Italian immigrants started to mirror those of the American Catholic laity, some third generation Italian-Americans hold on to some of the traditional beliefs of their forebears. Included here are the devotions to specific saints that their families revere and participation in feasts that honor those saints who appeal to a broad spectrum of Italian-Americans.

Economics

The Old Country: Economics

At the time Italians were migrating to the United States, Italy was a land that couldn’t support its poorest citizens. It was a land of chronic poverty. In fact, Italy encouraged its contadini (peasants), as well as its urban poor, to emigrate. The economic problems, shortages, and lack of opportunities were constant reminders that Italy’s poor could no longer survive and find hope in their homeland. Hence, five million Italians would emigrate from Italy between 1880 and 1924 seeking their fortune elsewhere. Economically, Italy was the past and America was the future—if not for the first generation then it would be so for their descendants.

New Lives: Economics

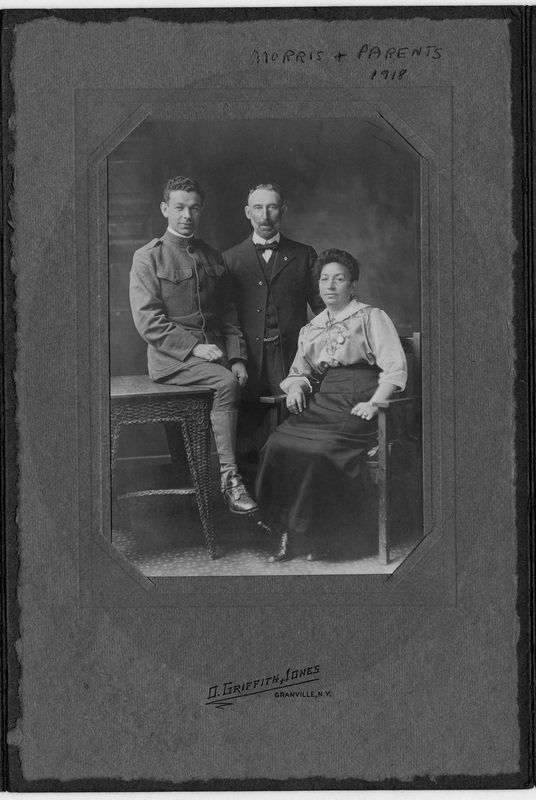

By the time the Italians arrived in the Slate Valley at the beginning of the twentieth century, they along with others would become the younger replacements for the aging Welsh and Irish quarry workers who had preceded them. While the vast majority of Italian immigrants to the United States were from southern Italy, the Italian immigrants who worked in the quarries were from Northern Italy primarily. Chain migration, drawing immigrants from Italy, brought the migrants to certain areas of America based upon job opportunities. Once the “chain” was begun it kept feeding upon itself drawing immigrants from certain areas of Italy and from certain job descriptions. Thus, the early Italians to Slate Valley encouraged other Italian family members and paesani (town folk) to join them in this part of America for the opportunities of the New World. While the earliest Italian migrants worked in the quarries, there were some Italians who opened businesses that catered to the Italian-American enclave as well as to the other families in the area.

Next Generations: Economics

For those Italian-Americans of subsequent generations, the economic promise of America that their forebears once envisioned became a reality. For those Slate Valley Italian-Americans who continued to work in the slate quarries or those who branched out into other endeavors, they became more successful financially. The Slate Valley Italian-Americans found employment in other businesses as well as starting their own businesses. From the third generation onward, many of these Italian-Americans became successful in white-collar and professional careers.

Education

The Old Country: Education

For the Italian poor, education was not considered a viable option. For, to stay in school for too long a period of time deprived the family of the youngster’s work efforts and the ability to bring extra money into the family’s pockets. The peasants were discouraged to pursue an education by the religious and political leaders as well as their parents. Educational achievements were viewed as an erosion of family values. Peasant families looked down upon education as an idle pursuit for the children of the rich. To the poor of Italy, both in southern and northern Italy there was no precedent for their children moving up the social ladder through educational successes. To these people of the soil, survival resulted from their physical toil and not from “wasting time” in school caught up in “frivolous” pursuits.

All of these factors combined in the millions of Italians migrating to the United States to find opportunities for their successes and for the economic and social betterment of their offspring.

New Lives: Education

While there were those Italian immigrants that wanted their children to benefit from an American education, there were those who were distrustful of the educational system. The latter group feared that the schools would indoctrinate their children with values that would oppose the Italian values that the parents wanted to instill in their children as well as diminishing the authority of the family. No matter what stance the families took, the harsh reality was that children were often taken out of school at an early age so that they could work and earn a wage that would benefit the family financially. Nevertheless, for those children that stayed in school their educational experience started the assimilation process in earnest. Even give this educational experience, there were those Italian-American children who learned how to integrate the Italian and American parts of their hyphenated existence.

Next Generations: Education

It is with the third and fourth generation descendants of the Italian immigrants that there is an increase in academic achievement at the undergraduate, graduate and professional degree levels. Part of the assimilation process and the quest for the American Dream is the goal that one’s children will surpass the achievements of their parents. Even if this achievement directs the children away from their parents’ way of life, it is now seen as the way things happen in America. With this increase of academic attainment, the contemporary Slate Valley Italian-Americans honor those relatives who came to the United States to work and to give their offspring the opportunities and possibilities that America would offer.

Currently Closed. Click here to learn more about our hours.

Research & programs by appointment only

The Slate Valley Museum's programs are made possible by the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Kathy Hochul and the New York State Legislature.